If flowing water could tell a story, then the Tsolum River has an epic saga to tell.

2015 marked a major milestone in the river’s life history when 100,000 pink salmon returned to spawn – the largest return since 1935.

Not bad for a river that in the mid-1990s was deemed one of British Columbia’s most endangered thanks to the damage left behind by a copper mine on the shoulder of Mount Washington. The Mount Washington copper mine operated for just a few years in the mid-1960s before going bankrupt. It is a poster child for how to do everything wrong with a mine. But how the Tsolum was salvaged in the years since its closure is a testament to what dogged community effort can achieve.

Let’s face it. Hard rock mining is a big, dirty, and environmentally complex business. Nobody wants an open pit in their backyard.

Yet, it’s hard to escape the truth that so much of what we rely on in modern life is dependent on metal. There’s gold in the electronic circuitry of our smartphones, molybdenum in the steel that forms the edges of our skis, and aluminum in our bike frames. On it goes.

Vast fortunes are made digging this stuff from the ground, with profits shovelled into the pockets of shareholders and promoters. However, too often, the public is often left holding the bag for costly cleanup efforts that can last decades after a mine ceases operation.

The physical footprint of the Mount Washington mine is modest by mining standards – some pits and tailings on Mount Washington’s north side, and the concrete foundations of the old mill visible lower down the mountain. The real, more serious footprint is invisible – acid rock drainage or ARD.

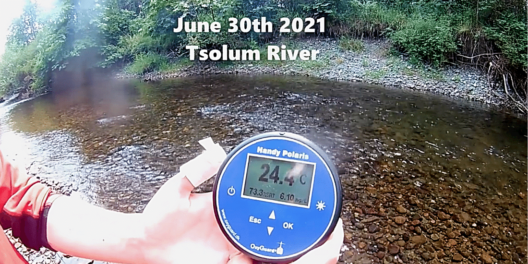

Acid rock drainage occurs when rock waste and tailings from sulphide minerals like copper are improperly stored. When exposed to air and water, a natural chemical reaction can produce sulphuric acid that contaminates streams and rivers with acidic run-off rendering them virtually uninhabitable to fish.

Managing this waste requires a commitment that lasts much longer than the commercial life of a mine. But, unfortunately, few miners stay for the long haul, and BC’s lax regulations and enforcement doesn’t hold them accountable. That’s what sacrificed the Tsolum.

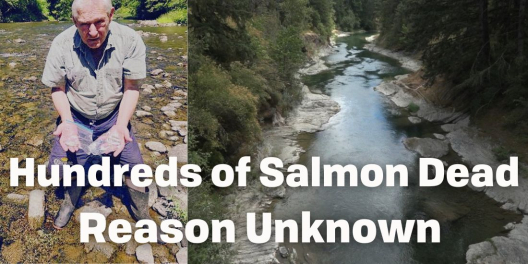

Bringing the Tsolum back to life took a monumental effort on behalf of longtime conservationists like Wayne White, the late Charles Brandt and a host of other local citizens behind the Tsolum River Restoration Society – and millions of dollars.

In 2009, after years of trial and error, a solution was found. A geo-membrane liner was placed over the offending parts of the pit and waste dumps. In addition, a drainage system was built to capture contaminated seepage.

It’s technical stuff, probably boring to most people unless they happen to be geochemists. But these efforts have controlled the levels of copper leaching, and coupled with ongoing in-stream habitat enhancement, have rescued the Tsolum River from the brink.

When you read the financials of mining companies like Canadian-based global powerhouse Barrick Gold, especially when metal prices are high, it’s easy to get seduced by the long string of zeros following the digits on the profit side of the balance sheet.

Yet, they are rarely without controversy. The mine in Faro, Yukon, once the world’s largest open-pit lead-zinc operation, has so far cost taxpayers more than $1 billion in remediation costs since operations shut in 1993.

It took decades to tame the ghost of the Mount Washington mine.

The health of a fish river says much about how we live upon the land. But, regrettably, we can’t fabricate new salmon streams.

The Tsolum River was nearly lost forever thanks to a brief pulse of copper mining on Mount Washington that never should have happened. More than 50 years later, the river is finally returning, thanks to the dogged efforts of some local heroes