We don’t normally think of grizzly bears as our neighbours. These days, finding a bear in your yard can be pretty scary. But for the people who have lived on BC’s northern coast for the past 14,000 years, grizzly bears are the buddy next door who really likes to eat and sleeps a lot in the winter.

At least, that’s what researchers discovered when they started looking through DNA samples from bear hair.

I know—it sounds weird. Bear hair. But it turns out that’s a good way to get bear DNA without wrestling a grizzly.

Researchers put piles of stinky fish goo in specific spots around the study area. Then, they surrounded the piles with little barbed wire fences. When the bears went to check out the smell, the fence snagged bits of fur without hurting the bear (or the researchers).

The researchers got hair samples from a couple of hundred bears, and when they put those bits of DNA on a map, what they discovered was amazing.

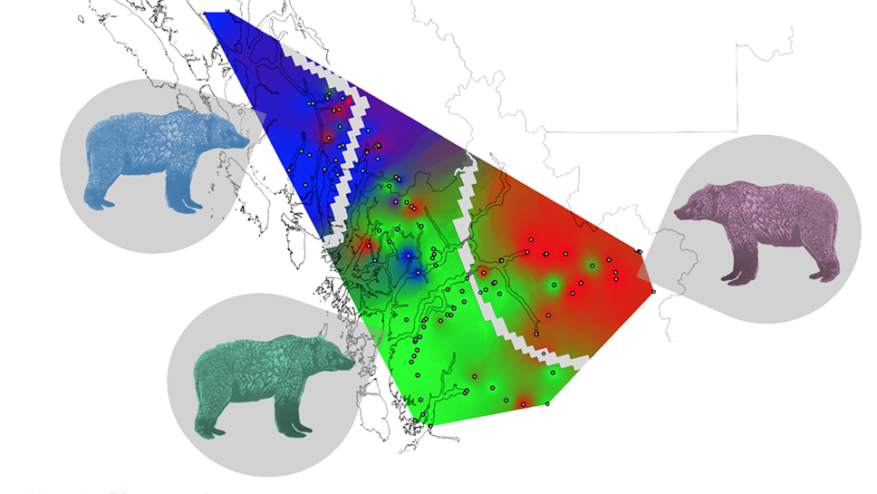

It turns out the DNA from the bears overlapped with the language families of Indigenous peoples who have lived on the North Coast for thousands of years.

What does this look like in real life?

Well, there are basically three bear “families” in the study area. I don’t just mean brothers and sisters. I mean siblings, cousins, great aunties twice removed, the whole shebang.

And each family lives on its own big piece of land. So they are three groups of bears who have been around each other so long that they’re all related, and outsiders don’t really “marry in,” ya know?

When the researchers figured out where those bear families live, the land matched the territory of three Indigenous language families—the Tsimshian, Northern Wakashan, and Salishan Nuxalk.

And what is a language family?

They are groups of languages with a common ancestor. So people in these families might not be blood-related, and they might have different words for some things, but they can generally understand each other.

So for thousands of years, these big bear families and people families grew up together. They shared the same land.

The wildest part of this story is that there are no physical barriers to keep the bear/human families apart. There are no mountain ranges, no big rivers, and no deserts between them. All three overlapping bear/human families are just kind of… separate.

But how?

Jesse Popp, an Indigenous environmental scientist at the University of Guelph, told Science Magazine that the findings are “mind-blowing.”

But Jenn Walkus, a Wuikinuxv scientist who helped with the study, isn’t surprised. She told Science Magazine that she grew up in Rivers Inlet and saw that people and bears need a lot of the same things. We both need lots of space, food, and other resources like salmon.

For now, the researchers figure that the land shaped the people and bears in similar ways. And there may have been enough salmon and space for everyone, so they didn’t need to move around.

That situation might be changing. This study happened because grizzlies started moving from the mainland onto islands off the coast, and no one knew why. No one has a real answer to that question. But, here on Vancouver Island, I can tell you we’d like to know.

Lauren Henson is the lead author of this study. She is a researcher at the University of Victoria and the Raincoast Conservation Society. More than a dozen researchers from 10 universities and First Nations helped put the study together.

The researchers thank the more than 100 people who helped collect grizzly bear hair samples. They are especially grateful to the Gitga’at, Haíɫzaqv, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Wuikinuxv, and Nuxalk leadership and Guardian Watchmen programs that made the study possible.

They dedicated their work to the late Nuaqawa (Evelyn Windsor), who taught them that people learned their language and way of life from the bears.

To read the whole study, visit Ecology and Society.